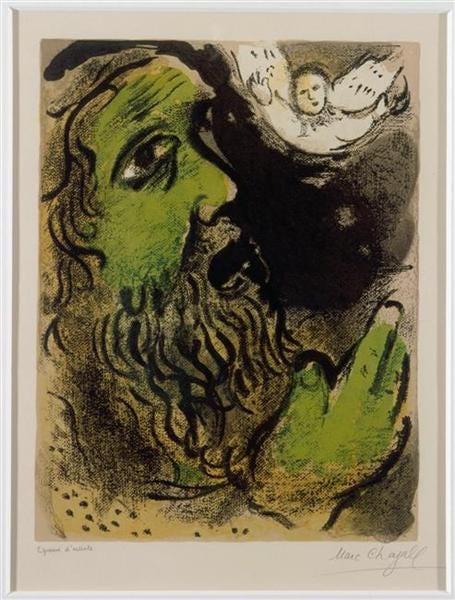

(Job Praying, Marc Chagall, 1960)

Glass of Blessings

God’s ordinary course is that His people in this world should be in an afflicted condition.

— The Rare Jewel of Christian Contentment by Jeremiah Burroughs

We say that a person who endures under affliction has the patience of Job, but Job may disagree with that statement. He would point us to Scripture which shows he struggled through his trials. He was angry with friends, bitter, discouraged, dismayed, and “His only hope was that God would crush him” (Job 6:9). Job would tell us he wasn’t patient, he was in anguish. But somehow, over the course of his suffering, he became the man of patience the world recognizes.

In Deuteronomy 13:4, Moses tells the people of God, “You shall follow the LORD your God and fear Him; and you shall keep His commandments, listen to His voice, serve Him, and cling to Him.” The entire believer’s walk can be summed up in that one phrase, “cling to Him.” All the other commands in the verse flow naturally from clinging to God. Jesus says the same thing in different words, “Abide in me, and I in you. As the branch cannot bear fruit by itself, unless it abides in the vine, neither can you, unless you abide in me” (John 15:4). Job became patient as the Spirit drew him to cling to God.

In his poem, “The Pulley,” 17th-century English poet George Herbert shows the many blessings God provided for Adam and Eve in the Garden, nearly every blessing:

When God at first made man, Having a glass of blessings standing by, “Let us,” said he, “pour on him all we can. Let the world’s riches, which dispersèd lie, Contract into a span.”

But because God knows the propensities of man, He withheld one significant blessing. Herbert’s poem continues:

When almost all was out, God made a stay, Perceiving that, alone of all his treasure, Rest in the bottom lay.

Herbert says that rest, a jewel of a blessing, would eventually work against Adam and Eve because if they had all blessings and rest with them, it would keep them from seeking God and:

He would adore my gifts instead of me,

Herbert’s poem shows that instead of rest, God gave Adam and Eve a better gift:

Yet let him keep the rest, But keep them with repining restlessness; Let him be rich and weary, that at least, If goodness lead him not, yet weariness May toss him to my breast.

The heart of the matter for Job, the heart of the matter for us is that we rest in the things God gives us rather than in God. When these things are taken away, we say with Job, “I have no peace, no quietness; I have no rest, but only turmoil” (Job 3:26). The Spirit of God used affliction to move Job to cling to God by taking his anger, bitterness, frustration, and grief to Him in prayer, in devastation of heart, and, increasingly, in worship. Herbert uses the word “repining,” which he may have understood in the 16th-century sense of repenting. Job’s repining restlessness – the Spirit’s help to turn him from each lapse of trust – is what cast him to the heart of God.

This is how Job became patient, it’s how we cling to God. It’s why Herbert uses the pulley, a simple machine, to title his poem of deep spiritual significance. Affliction lifts our hearts to God and transforms the God-given weight of restlessness into “a far more exceeding and eternal weight of glory.”

I was glad to see your post in my box. I enjoyed your past posts and hoped you’d be back.