Gracious Unfairness

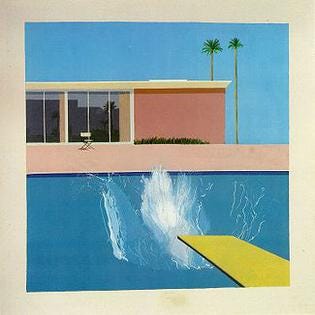

(Painting, A Bigger Splash, David Hockney, 1967, acrylic on canvas, Wikipedia)

“Every day is a gift. It's just, does it have to be a pair of socks?” —Anthony Soprano

After nearly dying from a gunshot wound inflicted by his uncle, Tony Soprano discovered a new vibrancy to life. He was deeply moved by his wife, Carmela’s, watchfulness and care through his ordeal, and was overjoyed to have more time to spend with his daughter and son. But as his strength and health returned, Tony morosely quipped the line about socks when explaining to his therapist, Dr. Melfi, how his pursuit of other women was being strangled by his newfound gratefulness for Carmela.

In the first season of The Sopranos, I had hope for this complicated character. Tony was a murderous, blackhearted thug but he was also warmhearted and generous. I could not tell if his love for family would conquer his love for so many other things. But I thought something promising might be stirring when he became captivated by paintings. He assumed the one outside Melfi’s office was a “psychological picture” to trick him. Melfi asks, “What does that picture say to you?” Tony responds, “It says, ‘Hey asshole, we’re from Harvard, and what do you think of this spooky, drepressin’ barn and this rotted out tree we put here?’” Melfi helps Tony see that the painting is reflecting his turmoil over losing his good friend and mob boss, Jackie Aprile, to cancer. We know this by the way Tony shouts his favorite expletive at Melfi and slams her door as he leaves. Another painting that mystified Tony was in his cumare’s apartment. “What’s that paintin’ mean to you?” he asked Irina, scrutinizing it as he dressed. “Nothing,” she says through her Russian accent. “It just reminds me of David Hockey [sic].”

I think if Tony had pursued these shadows of that indefinable something that speaks to us—sometimes shakes us—from paintings and poems and literature, maybe he could have extracted himself from the gangster quagmire. Maybe that’s biting off more sfogliatella than we can chew.

But isn’t it true that art, in all its forms, is sometimes how God, the one who speaks through images and metaphor, draws our attention to him? Isn’t this a bounty that we, blackhearted as we are, really have no claim to? Why is there art in the first place? Why has it been saved throughout history? So much of the art we love would have been lost if not for the sometimes quixotic, sometimes manic rescue by those who felt called to preserve it. Van Gogh’s paintings rose to prominence after his death because his sister-in-law, Johanna Bonger, carefully sold and curated them; more than a thousand works of art that could have been destroyed in WWII were saved because Cornelius Gurlitt hid them and hermited himself with them in his Munich apartment for fifty years; Emily Dickinson’s family saved for us the 1,800 poems found in her room in tidy bundles after her death. Isn’t art a hint of God’s rescue? Just one example of the gracious unfairness he extends to us to point us to what lies beyond us, and within us?

I like to think that the ending of The Sopranos is left to our imaginations. In my version, I imagine that sometime after the family’s nice meal together, Tony does begin to see something more in paintings and in a poem or two. He starts going with Carmella on her trips to museums, and engages A.J. in the existential questions that were chasing him. I like to think his pursuit of questions and art wakes him to this gracious unfairness. Maybe the things art can say would have made a difference. Maybe he would have found that life’s gifts are far grander than socks.